Book Review

In the Wake of the Graf Spee by Enrique Dick. Translated by Marilyn Myerscough and published in English 2015, WIT Press.

Original Spanish edition Tras La Estela del Graf Spee, first published in 1999.

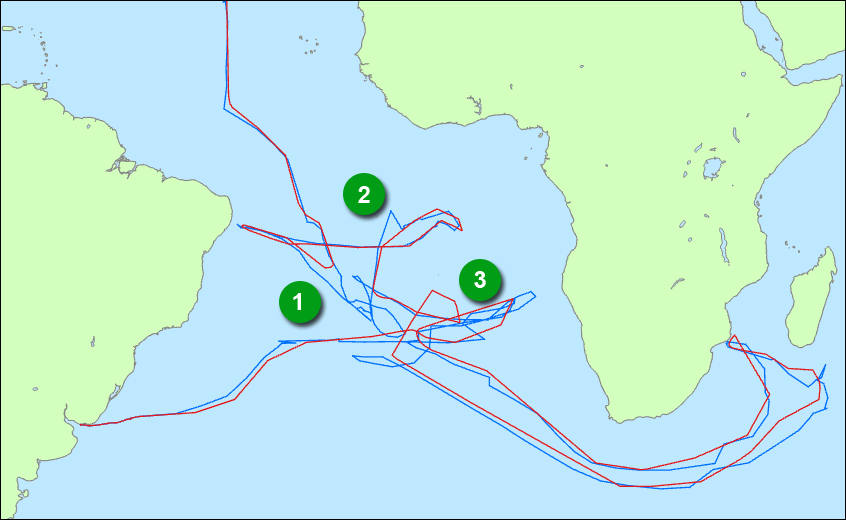

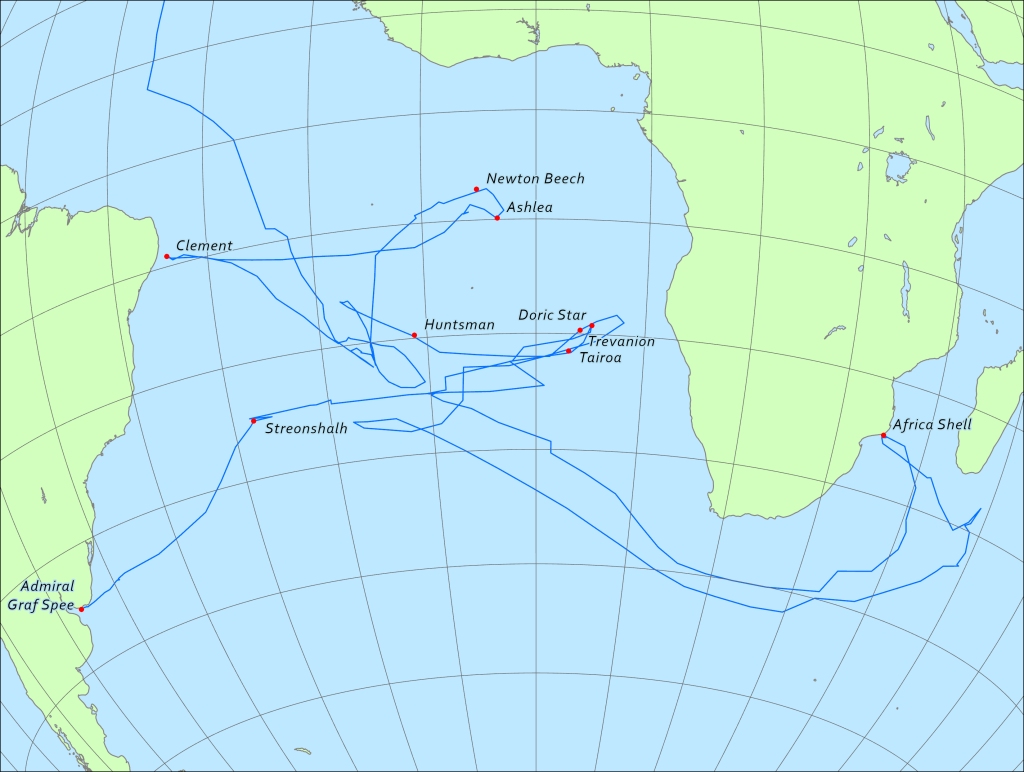

When World War II began in September 1939, the German pocket battleship Admiral Graf Spee was already heading to its assigned patrol area the South Atlantic, where it would target Allied merchant vessels. The ship’s three-month campaign, which included the sinking nine merchant ships, a fierce battle with three British cruisers off the coast of South America, a retreat to Montevideo, and the sinking of the Admiral Graf Spee, is extensively documented. Most accounts focus on the actions and decisions of the Graf Spee’s commander, Captain Langsdorff, whose choices led to the ship’s demise. Typically, these narratives conclude with the ship’s sinking near Montevideo and Captain Langsdorff’s subsequent suicide in Buenos Aires. Eric Grove’s The Price of Disobedience: The Battle of the River Plate Reconsidered is a notable exception, as it also examines the fate of the ship’s remains up to recent times. However, even Grove’s work, like others, provides scant details on the crew’s experiences post-1939, some of whom returned to Germany to continue the war effort, while most were interned in Argentina for the duration of the conflict.

Enrique Dick’s In the Wake of the Graf Spee offers a fresh, though personal, perspective on this historical episode. While it recounts the Admiral Graf Spee’s voyage, the Battle of the River Plate, and the ship’s sinking, its primary focus is on the crew, particularly Heinrich Dick, the author’s father, who served on the Graf Spee. Rather than providing a complete historical account or a strict biography, Dick narrates the events surrounding his father’s internment in Argentina. The book includes details about the Graf Spee and its war patrol, but these are presented as pivotal moments that drastically altered the lives of Hein and his fellow crew members, setting them on an unexpected journey in Argentina.

The narrative centers on the five years the crew spent in Argentina, initially as internees and later as prisoners of war. Dick focuses on 200 crew members who were sent the small town of Capilla Veija, 750 km northwest of Buenos Aires, where they built their own internment camp and integrated with the local community. The community was largely welcoming, and by the war’s end, some crew members had married local women, hoping to make Argentina their permanent home. However, their forced return to Germany after the war delayed these plans. Heinrich Dick, who married shortly before being deported, spent four years in Germany before rejoining his wife and her family in Argentina where he remained until his death in 1992.

Dick’s portrayal of his father is affectionate and shifts between a personal narrative and a broader, more objective perspective. Although his dedication occasionally leads to overly detailed descriptions, it paints a vivid picture of the 200 men who found themselves stranded in a foreign land. The book primarily focuses on their lives in Argentina, with the war serving as a backdrop rather than a central theme. It suggests that these men were fortunate to find a welcoming community, far removed from the widespread devastation of the war.

Dick’s early life in Germany, his acceptance into the Kriegsmarine in 1938, and his year of service onboard the Graf Spee are covered in the first 110 pages of the book. The remainder of the book focuses on Dick’s time in Argentina and includes some gratuitous coverage of commemorative events marking the sinking of the Graf Spee in 1989, 1999 and 2009. Also included is a technical appendix covering all aspect of the ship.

This book is not a critical assessment of the Graf Spee, it’s commander and crew or of any of the events that occurred in late 1939. The ship, in fact, comes off as a technical marvel for its time. Any of its known shortcomings – the MAN engines that caused severe shaking throughout the ship when run at high speeds, its poor seakeeping and light armour – are not mentioned at all. This book will disappoint those looking for additional insight in the Battle of the River Plate and the decisions that were made. Though this book fails to provide a complete account of what happened to the crew of the Graf Spee after the scuttling of their ship, it does provide a lovely, peaceful snapshot of life during the 1940s, far from the destruction and chaos that overtook much of the world during that time.